Key Ingredients of a Walkable City

An important concept in urban development is what we call the “3 Ds”: Density, Diversity, and Design

An important concept in urban development is what we call the “3 Ds”:

(1) Density

(2) Diversity

(3) Design

To build a walkable and sustainable future, we need to implement all of them, simultaneously.

Density refers to the number of people and building square feet per acre. Achieving certain minimum densities helps support more transit options and businesses, promotes municipal fiscal balance, helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and reduces destruction of forest and farmland.

But increasing density by itself, and without consideration to other elements of urban development, is inadequate and a policy failure.

Diversity refers to the diversity of uses. For example, instead of hundreds of acres of houses, there is a mix of homes and businesses woven throughout the neighborhood fabric.

People are able to reach a variety of different residential types, commercial uses, employment opportunities, child care, services, travel modes, and civic spaces within a short distance.

Diversity can also refer to diversity of people, generational, economic, racial, ethnic, ability, familial… Cities should be built by and for the range of groups that live in them (and want to live in them). That includes maintaining permanent supplies of social housing, prioritizing very low wealth families, people on fixed incomes, and other vulnerable populations.

Cities can and should ensure a diversity of uses as they grow and measure and track progress over time.

For example, cities should maximize the percentage of residents able to make a 5-10 minute walk (known as the “pedestrian shed”) to playgrounds and green spaces, grocery stores, transit stops, and jobs.

Design is key to equitable and sustainable development, and an area often overlooked in Durham.

The devil really is in the details here so let’s walk through some examples of key sustainable urban design concepts.

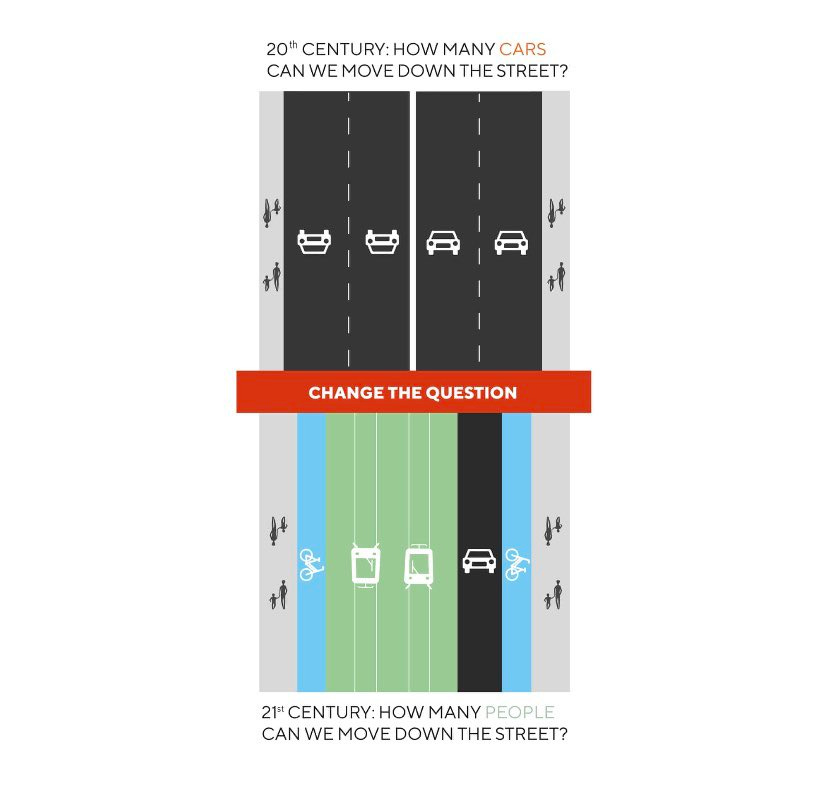

STREETS come in many shapes and sizes. Today, most streets are designed to move vehicles and all other modes are secondary. This means most of the street right-of-way width (80-100%) is allocated to vehicle space. To expand transportation options for residents, we can look at other evidence-based practices that enhance our infrastructure.

One best practice for U.S. streets is to allocate 50 percent of the street width for moving vehicles and the other 50 percent for everybody else: parked cars, bikes, pedestrians, seating areas, etc. That may still seem like a lot of vehicle space, and it is plenty, but using the 50 percent rule would be a balanced shift toward expanding realistic, safe travel options.

In some places, we could imagine an even greater proportion of street width be allocated for non-automobile modes of transportation.

SIDEWALKS should be wide enough to accommodate outdoor seating, window shopping, walkers and rollers, and street trees and lights.

Street trees should generally be located adjacent to the curb to provide a buffer from the street and shade for pedestrian comfort.

CYCLE LANES should be physically buffered from moving traffic by things like curbs, planters, or parked cars.

Parked cars aren’t super fun to look at but serve a key role in providing convenient parking while also creating a sturdy buffer from moving vehicles.

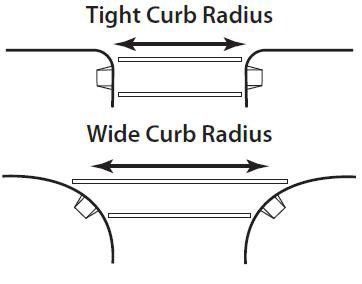

One of the most overlooked details of urban design is the curb radius at street intersections. A wide curb radius (>15 degrees) means it’s a wide curve and a tight curb radius (5-15 degrees) means it’s a short curve.

The small radius is pedestrian-oriented because it requires cars to slow down and shortens the distance for people to walk between intersections. The high radius allows vehicles to speed around the corner and elongates the crossing distance. Next time you walk, see if you notice the curb radii at intersections.

ALLEYS are important parts of sustainable cities.

Alleys:

Eliminate the need for front driveways and garages

Make buildings more human-oriented, allowing for porches and shop fronts facing the street

Move trash and utilities to the back

Reduce needed street width

Make accessory dwelling units more feasible

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder but the bulk, design, and orientation of buildings is critical in determining whether each contributes to a sustainable urban form or not.

One key piece of a building of any size is the design of the first 14 feet of the ground floor because this is what human beings see and experience as they navigate the city. The design determines whether a person feels safe or not, feels comfortable or not.

There are many - and I mean many - ways to design pedestrian-oriented buildings.

Ideally, they should be human scale, permeable (people can see and move into and out of the building), and contain texture rather than blank walls.

Learn more about pedestrian-oriented building design here.

The easiest way to create great cities is to design and build them right the first time. Redevelopment is expensive, inefficient, and sometimes controversial. Most large sprawling suburbs will be nearly impossible to retrofit for walkability. But in some places, it is never too late to fix what we have gotten wrong in the past.

So there it is, an incredibly brief and incomplete introduction of the 3 Ds of sustainable urban development and why they are important if we want to shift from an auto-dominated society to one that is much more sustainable and inclusive. Thanks for sticking with it!

This thread was very design focused, and left out all the important social, democratic, and participatory elements of sustainable cities. Those are essential too, particularly in cash-strapped neoliberal cities where limited resources need to be used wisely.

Durham is not doing many of these things throughout the majority of our new growth. Each day brings more long term unsustainable development, especially sprawl, with negative consequences for future generations.

We have a lot of work to do and it’s an uphill battle!